The Time Loop Paradoxes That Keep Sci-fi Fans Hooked

Time loops challenge logic but make for great storytelling. This issue explores paradoxes in "The Terminator," "Timerider," and "Primer," with trivia from "Predestination," "Interstellar," and more.

This Week in Classic Science Fiction — The Birth of John Connor

In the grim future of "The Terminator" (1984), John Connor is humanity's last hope. But his birth —February 28, 1985— exists in a tangled web of fate, a paradox where the past and future fold into one another.

John's existence is the result of a closed time loop, a rare storytelling mechanism that bends causality itself.

In the post-apocalyptic war against Skynet, he rises to lead the Resistance, striking blow after blow against the machines. Desperate to erase their greatest adversary before he can even rise, Skynet deploys a cybernetic assassin, the T-800, back to 1984. Its mission is simple —kill Sarah Connor before she can give birth to the man who will one day bring down Skynet.

But time has its own designs. To counter the Terminator, John sends Kyle Reese —his most loyal soldier— back to the same year to protect Sarah and unwittingly become John's father, closing the loop. Thus, the future births itself, releasing an inescapable cycle of war and survival.

Unlike other time-travel narratives where history can be rewritten, "The Terminator" suggests an immutable destiny. John exists because of the war, yet the war only happens because John exists. His life is not his own; instead, it is dictated by events set into motion before he was even conceived.

This deterministic structure gives "The Terminator" a weight that other time-travel stories lack.

Even in later sequels that attempt to alter fate —"Terminator 2: Judgment Day" (1991), "Terminator: Dark Fate" (2019)— John remains a symbol of inevitability. He is the man who must rise, again and again, to fight the machine overlords. His birth is both the beginning and the end of Skynet's nightmare.

This week, as we recognize February 28, 1985, we celebrate not just the birth of a character but one of science fiction's most compelling paradoxes. John Connor is a man forged by time itself, a figure locked in an eternal struggle where past and future converge.

Time Loops in Science Fiction

Time loops defy logic. A person shouldn't be able to cause their own birth, witness their own death, or exist without an origin. And yet, science fiction has embraced these paradoxes for decades.

Audiences rarely demand scientific accuracy when it comes to time travel, but they do expect internal consistency —rules that make sense within the story's own framework.

Some time loops reinforce destiny, as in "The Terminator," where John Connor's rise depends on an unbreakable cycle of events. Others lean into irony, like "Timerider," where Lyle Swann unwittingly becomes his own great-great-grandfather. Stories like "The Time Machine" suggest that time resists change, while films like "Primer" embrace the chaos of overlapping timelines.

Despite their contradictions, time loops captivate us. They challenge our understanding of causality and fate. More importantly, they make for great storytelling. Whether serving as a metaphor for destiny or creating narrative tension, time loops have become a staple of science fiction.

John Connor

If time travel stories have a gold standard for predestination paradoxes, it's "The Terminator." As mentioned above, the film doesn't just introduce time travel as a plot device —it builds its entire premise around a closed loop of fate.

John Connor, the leader of the human Resistance against Skynet, exists only because he sends his most trusted soldier, Kyle Reese, back in time to 1984 to protect his mother, Sarah Connor. Reese fulfills his mission, but in the process, he becomes John's father. The future creates the past, locking John into an unbreakable cycle. There was never a version of history where Reese didn't travel back in time, never a moment where John's birth wasn't guaranteed.

The audience accepts this paradox because the story is internally consistent. John Connor must be born, so he will be born.

John Connor's paradox is one of science fiction's most famous examples of time shaping itself. It's not about altering the past—it's about fulfilling it.

The Curious Case of Lyle Swann in "Timerider"

While "The Terminator" presents a tightly structured predestination loop, "Timerider: The Adventure of Lyle Swann" (1982) takes a more ironic —and arguably unsettling— approach to time travel. Unlike John Connor, whose existence is engineered by necessity, Lyle Swann stumbles into his paradox without ever realizing it.

Swann, a motocross racer, accidentally rides into a government time travel experiment and is sent back to 1877. Stranded in the Old West, he navigates life among outlaws and frontier settlers. One of those settlers, an attractive woman named Claire Cygne, becomes romantically involved with him. By the time Swann finds a way back to his own era, the film drops a revelation. Claire is actually his great-great-grandmother.

The film never thoroughly explains whether his presence in the past was always meant to happen, but the implication is clear —his ancestry is a closed loop.

Swann's paradox is a classic example of a self-fulfilling timeline that exists without a clear point of origin. Swann isn't a soldier fighting for the future; he's a racer caught in a causality trap. The audience may suspend disbelief for the sake of the adventure, but the implications are inescapable —his past was always going to include himself.

H.G. Wells' "The Time Machine" and the Illusion of Control

Long before films like "The Terminator" and "Timerider" played with time loops, H.G. Wells laid the foundation for time travel storytelling with "The Time Machine" (1895).

While Wells' novel does not feature a strict time loop, it introduces the idea that time may resist change —an idea that later adaptations twist into something more paradoxical.

The original novel follows an unnamed Time Traveller who journeys to the distant future, witnessing the downfall of civilization and the eventual heat death of the Earth. Unlike modern time-travel stories, Wells does not present a loop or a paradox —his traveler moves forward through time without interference in his past. However, later adaptations, particularly the 2002 film version of "The Time Machine," reframe the story through a predestination paradox.

In the 2002 adaptation, Dr. Alexander Hartdegen builds his time machine after the tragic death of his fiancée. Hoping to change the past, he repeatedly attempts to save her, only to watch her die in new ways each time.

The film ultimately suggests that her death is unalterable because it is the very event that drives him to invent the time machine in the first place. If he succeeded in saving her, he would never have built the machine —thus, the paradox would unravel itself.

This idea —that time enforces its consistency— mirrors the loops seen in "The Terminator" and "Timerider." Even when characters attempt to rewrite their fates, time resists. The protagonist of "The Time Machine" struggles against a force that refuses to bend. His loop is not about self-creation but self-destruction, a reminder that in some time-travel stories, the past is a trap that can never be escaped.

"Primer" and the Confusion of Infinite Loops

If "The Terminator" presents a clean predestination paradox and "Timerider" plays with ironic ancestry, "Primer" (2004) takes time loops to their most tangled extreme.

Shane Carruth's indie film is infamous for its complexity, offering a version of time travel where characters loop back so often that the original timeline is nearly impossible to trace.

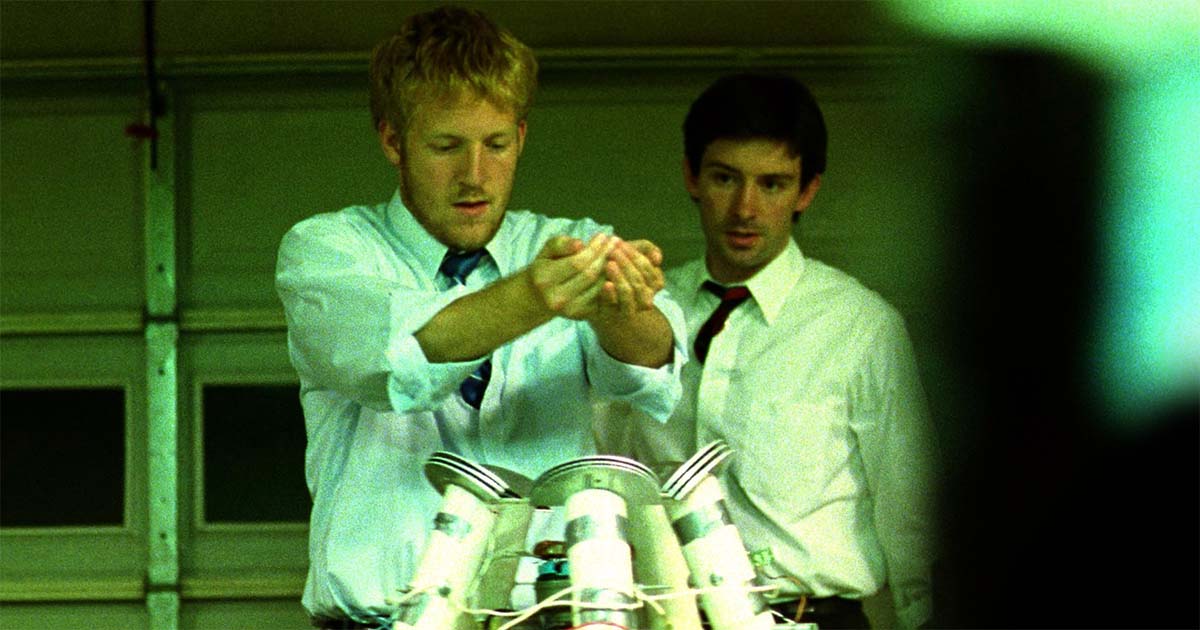

The story follows two engineers, Aaron and Abe, who accidentally discover a way to travel back in time.

As the protagonists experiment with their machine, they create duplicates of themselves, interacting with versions of their past and future selves in unpredictable ways. By the film's end, multiple versions of Aaron and Abe exist, each attempting to manipulate events while avoiding detection by their other selves.

The film treats time travel as a logical puzzle, where each decision spawns new branches of reality. Aaron and Abe create a scenario where timelines pile up on each other like an unsolvable equation.

The sheer complexity of "Primer" highlights a key difference in time loop storytelling. Some loops reinforce destiny, some emphasize irony, but others —like this one— illustrate the terrifying possibility that time travel would be impossible to control.

Why We Accept These Paradoxes

Time loops defy logic.

If John Connor's father was sent back in time by John himself, where did the timeline begin? If Lyle Swann unknowingly became his own great-great-grandfather, does his lineage have an origin at all? "The Time Machine" suggests that fate is inescapable, but who decided that rule? And in "Primer," how can a person move through time so many times that the original version of themselves ceases to matter?

These paradoxes should collapse under scrutiny. Yet, audiences rarely reject them outright. Why? Because, as mentioned above, a good time-travel story isn't about scientific accuracy —it's about internal consistency.

Science fiction, at its best, isn't about realism —it's about possibility. Time loops work because they create tension, mystery, and inevitability. Whether reinforcing destiny, revealing cruel irony, or creating sheer narrative complexity, they offer a way to explore the nature of time itself. The question is never how they work, but why they matter to the story.

Time Travel Trivia

- Predestination" (2014) is the film adaptation of Robert A. Heinlein's 1959 short story "'—All You Zombies—'." In this time loop, the protagonist is both his own father and mother.

- Director Christopher Nolan planted 500 acres of corn for "Interstellar" (2014) so the production could have actual farmland for key scenes. After filming, he sold the corn for a profit.

- "Edge of Tomorrow" (2014) is based on Hiroshi Sakurazaka's novel "All You Need Is Kill." The film initially kept that title but was changed for Western audiences.