Three Pilots, No Series, One Big Idea

Before "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," Gene Roddenberry spent the 1970s chasing a new future. "Genesis II," "Planet Earth," and "Strange New World" tried to carry his message forward—none succeeded. Here's why.

This Week in Classic Science Fiction — "Planet Earth" Aired

On April 23, 1974, ABC broadcast Gene Roddenberry's made-for-television movie "Planet Earth."

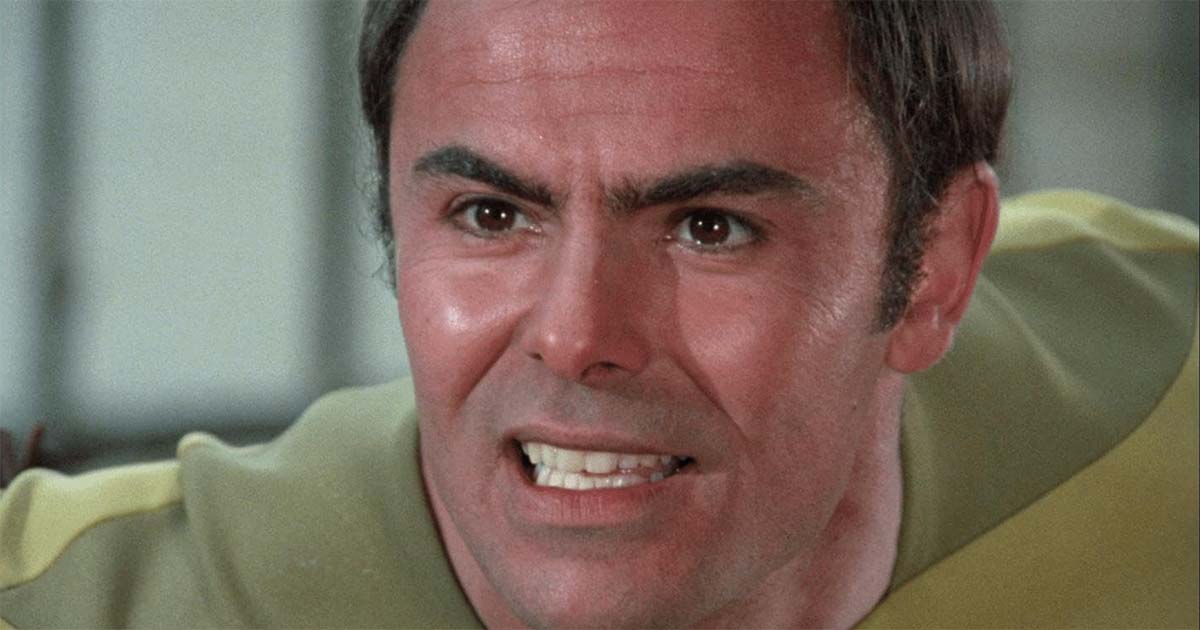

The film starred John Saxon as Dylan Hunt, a scientist working to rebuild civilization after a nuclear apocalypse. Set in the 22nd century, the story imagined a fractured America—ruled by matriarchal enclaves, violent warlords, and scattered remnants of knowledge.

"Planet Earth" was Roddenberry's second attempt to develop a new science fiction series following the original run of "Star Trek." Though the pilot never became a full show, it carried many of the same ideals—reason, cooperation, and moral courage in the face of chaos.

For fans of classic science fiction, it remains a curious footnote from a time when the future felt both far off and worth fighting for.

Sponsored by The Cosmic Tourist Sci-Fi T-shirt

Go Intergalactic Tourist Chic

Rock this tee featuring a visitor from beyond sporting shades and a Hawaiian shirt, snapping the ultimate Earth selfie. It’s proof that even aliens appreciate a good vacation photo op. Perfect for sci-fi lovers, travelers, and anyone who doesn't take life (or space travel) too seriously. Comfortable, unique, and a guaranteed conversation-starter. Grab this cosmic design now and show off your stellar sense of humor and style.

Shop Right Now

Roddenberry's Second Act

Gene Roddenberry spent much of the 1970s trying to recapture Star Trek's spark. He had created something singular in that series—a hopeful, orderly vision of the future grounded in what felt like moral clarity and scientific progress. But as the decade unfolded and American culture turned inward and cynical, Roddenberry's message met resistance. Three separate pilots—"Genesis II" in 1973, "Planet Earth" in 1974, and "Strange New World" in 1975—tried to carry that vision forward. None succeeded.

All three stories centered around Dylan Hunt, a 20th-century man frozen in suspended animation and revived in a post-apocalyptic 22nd century.

Each version placed him in the service of PAX, an organization trying to rebuild civilization. The setup changed slightly each time—different actors, factions, and nuances—but the core remained the same. Hunt was a man of reason in a broken world, trying to stitch it back together.

The concept had merit. It allowed Roddenberry to explore recurring themes like the tension between violence and diplomacy, the promise of human cooperation, and the persistence of truth. But in the compressed form of a television movie, these ideas were hard to develop.

The pilots had to introduce the world, define the characters, and resolve a conflict all in less than ninety minutes. That left little room for the kind of character arcs and moral dilemmas that had given "Star Trek" its staying power.

Casting posed another problem. John Saxon, who played Hunt in "Planet Earth," had a solid screen presence but lacked William Shatner's charisma and commanding idealism. There was no Spock, no McCoy—no cast dynamic to anchor the story. Hunt wandered alone through a shattered world, lecturing rather than leading.

More fundamentally, the country had changed. Roddenberry's vision was shaped by the optimism of the early 1960s when science and exploration still seemed like paths forward. By the mid-1970s, that hope had dimmed. The war in Vietnam had ended in humiliation. Watergate had poisoned public trust. Inflation, unemployment, and oil shocks had left many Americans wary of grand promises. Science fiction reflected this shift. Films like "Soylent Green," "A Clockwork Orange," and "Westworld" traded idealism for dystopia. Roddenberry was still writing about the future as a place worth building. The audience had started to see it as a warning.

If we give the message the benefit of the doubt, there was still the medium. His stories needed time and space to unfold. "Star Trek" had succeeded in syndication, where its moral framework had room to grow. The Dylan Hunt pilots were standalone efforts, each one a first chapter with no second.

And yet, they are worth watching. They show Roddenberry still working, still refining his ideas, still believing in man's ability to rise above tribalism and fear. These projects were not cynical, not cruel, not desperate. They were sincere. That sincerity may have been unfashionable, but it was never irrelevant.

Roddenberry would return at the end of the decade with "Star Trek: The Motion Picture." It was slower, more solemn, and perhaps too reverent for mass appeal. But it marked the return of the future he had once promised. The Dylan Hunt stories, meanwhile, remain on the fringes of his legacy—a set of lost roads that pointed, however faintly, toward the stars.

Roddenberry Trivia

- Gene Roddenberry flew B-17 bombers in World War II and survived a crash in the Syrian desert while working as a commercial pilot after the war.

- Before becoming a television writer, Roddenberry worked as a sergeant with the Los Angeles Police Department and wrote scripts under the pseudonym "Robert Wesley."

- In 1997, six years after his death, some of Roddenberry's ashes were sent into space aboard a Pegasus rocket—the first symbolic burial in orbit.